Carolina Oliveira

Stepping silently amongst the debris laden cobbled paving stones, the smoke streams and charred embers float through the air as burnt cars and buses smoulder softly, like remnants of a great volcanic storm, around me. Engulfed by the angry fires of the enraged mob the night before, these once quiet, charming, colourful backstreets of Brazil now lay blackened, sombre and unrecognisable; wounded in battle beneath a blanket of rubber bullets, glass shards, empty tear gas canisters and an echo of hope.

This was 2013, and as a Brazilian documentary filmmaker I was witnessing one of the largest ever social movements happening in the very city I grew up in in Northeast Brazil. Feelings of anger, sadness and revolt amplify within me. But as I turn my camera off, I realise that this has been an all too familiar sight across much of Latin America over the past 60 years.

Protester during the 2013 Mass Movements ahead of the World Cup in Brazil (photo by: Carolina Oliveira).

Between the 1960s and 1970s, Latin America cinema often explored the impoverished living conditions of sectors of society consistently overlooked by the government. These films sought to reflect the hardships, reality and political struggles of a population that felt disenfranchised and disenchanted with the status quo. This desire to document real life social issues, to give image and voice to those relegated to silence, propelled filmmakers towards documentary. To Latin American filmmakers, documentary became a promising alternative to the dominance of Hollywood narrative cinema.

Documentary film’s versatility in depicting real-life events, and its ability to navigate between educational, factual and historical cinema aesthetics and their narratives, enabled it to become the foundation for what Argentine filmmakers Octavio Getino and Fernando Solanas (1969) described as ‘cinema of liberation’. It was a style of cinema dedicated to the denunciation of injustice and political neglect, which focused on creating social awareness, the deconstruction of neo-colonialism and the exploration of matters of national identity.

The term ‘Third Cinema’ was coined by Getino and Solanas in their manifesto, ‘Towards a Third Cinema’. Some of the most important aspects of their work are embedded in the creation of one of the most influential films in Third Cinema documentary: La Hora de Los Hornos (The Hour of Furnaces, 1968).

Seen as one of the most important Third Cinema documentaries of the era, the film succeeds in depicting the socio-economic struggles and political discourses of Latin America in the 1960s. The film’s aesthetic form was as political as its content. Getino and Solanas brought forward the idea that revolutionary films should not fit within the parameters of the dominant Hollywood model. Otherwise, it would do nothing but conform to western norms, thus reinforcing the power of the status quo. Utilising an arsenal of non-conventional audio-visual techniques, the filmmakers deconstructed and rebelled against the conventional style of cinema seen in the West. Through the use of techniques such as distorted music, juxtaposition, experimental compositions, collage, animation and direct cinema, the Argentinian filmmakers found ways of production and distribution that differed from mainstream film industry methods.

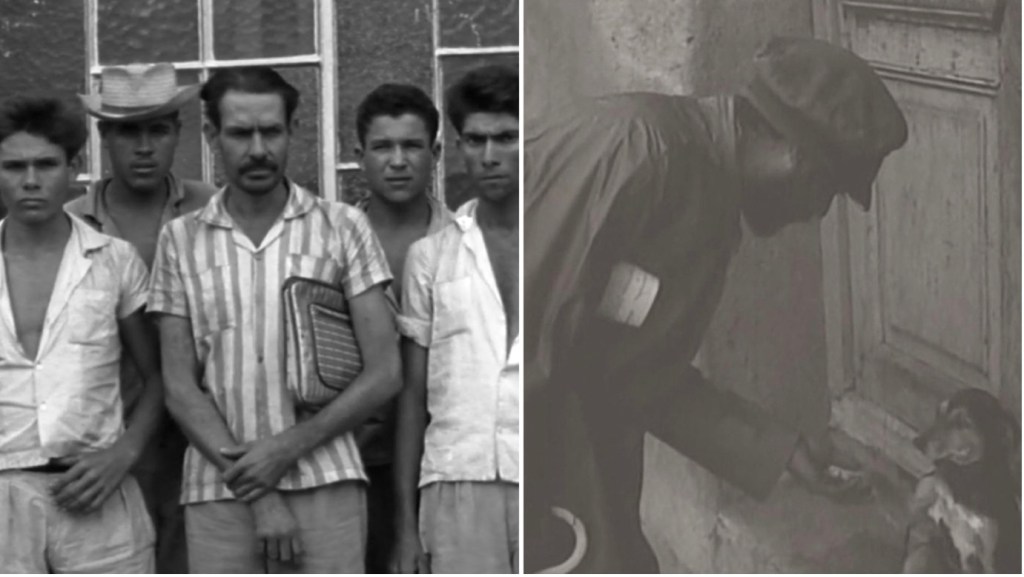

This new school of filmmaking, inspired new filmmakers to construct narratives that depicted the raw, intense realities faced within their own countries. This can be seen in Brazilian filmmaker Geraldo Sarno’s Viramundo (1964), a documentary that portrayed the harsh challenges faced by Brazilians in escaping the drought-ridden northeast regions of Brazil to migrate south to Latin America’s largest city, Sao Paulo, in search of work and a better quality of life. Equally, Uruguayan director Mario Handler’s film Carlos: Cine-Portrait of a Walker (1965) depicted the story of a vagabond, a man abandoned by the society he belonged to. Handler stated that the Latin American filmmaker “inevitably begins to become politicised, because the existing situation prevents him from being simply a filmmaker”.

Viramundo (1964) Carlos: Cine-Portrait of a Walker (1965)

Third Cinema rose to be a light in a time of darkness with documentary films which explored the possibilities of originality and creation that lived within untapped, undiscovered and innovative stylistic spaces. Films amplified the unheard voices of the working classes and the realities they faced day to day. Filmmaking in this part of the world became an act of rebellion, an honest interrogation of pressing issues with a view of promulgating political and social consciousness.

Due to the modern world’s multiplicity of identities and stories, Third Cinema has evolved to become Third Cinemas, a transnational medium where heterogeneity of cultures and identities become a force that strengthens and re-locates the Third Cinema movement within an expanding global community.

Brazilian-born filmmaker, Carolina Oliveira has been working in film and media production across the UK and Europe for over ten years. She is a former lecturer in Digital Media Production at The University of Brighton and Creative Video Production at the University of Sussex. Carolina holds an interdisciplinary PhD in Political Anthropology and Documentary Film, an M.A in Digital Documentary and a B.A in Media Studies.

Leave a comment