María Piqueras-Pérez

Black History Month offers an opportunity to celebrate the cultural achievements of Black Britons across multiple fields, including cinema. During the 1980s, three pioneering Black British film collectives—Ceddo, Black Audio Film Collective, and Sankofa—played a pivotal role in shaping Black British cinema and redefining the representation of Black experiences on screen. These collectives not only created groundbreaking films, but they also used cinema as a tool for activism and community empowerment. Their contributions remain relevant today, and revisiting their legacy allows us to reflect on how art and activism intersect to challenge hegemonic narratives and bring marginalised voices to the forefront.

The 1980s saw a significant transformation in British television and film, particularly with Channel 4’s commitment to diversity and the space for experimentation opened by the ‘Workshop Declaration Act’. This declaration enabled the collectives to receive funding and offered them a protected space to create radical and political cinema. What made them distinct was their commitment to portraying Black British experiences in ways that weren’t just oppositional, but artistically innovative. This created a form of “counter-hegemonic” cinema, which actively resisted the stereotypical, one-dimensional portrayals of Black Britons in mainstream media.

A Black British Cinematic Renaissance

By renaissance I want to highlight how there were black British filmmakers before them like Lionel Ngakane or Horace Ové but lacked funding opportunity. Workshops challenged the rigid bad/good dichotomy operating at the time as well as the idea that only avant-garde cinema could be considered good and oppositional cinema. This explains why Ceddo has been disregarded in academic circles even if their productions are highly experimental and oppositional (Williamson 1988). An example is the censorship faced by The People’s Account (1986).

The workshops tried to encourage audiences to find more complex ways of understanding the politics of ethnicity and showed how, as Martina Attille from Sankofa argued in conversation with critic Coco Fusco, “there are many aesthetics not just one. There are many experiences” (1986-7, 37). They engaged with latent issues in new and multiple ways such as race, identity and memory. As such, they inaugurated a Black British experimental Renaissance, which showed the many ways of being black in the Union Jack–to paraphrase Paul Gilroy (1987).

“I hid from my real sources, but my real sources were also hidden.”

One of the most powerful aspects of these collectives’ work was their focus on uncovering hidden histories. Through their productions they unveiled, through critical examination, alternative versions of unknown, overlooked, manipulated and suppressed pasts. As the off-voice of Sankofa’s Territories (1984) argues, “I hid from my real sources, but my real sources were also hidden.” They offered new ways of understanding the past through their visual reworkings, showing how they not only reclaimed history but also offered new ways of understanding it. In doing so, they centered Black British voices, deconstructed official history and encapsulated, as Time argues in Ceddo’s Time and Judgement “the circle of history they try to erase but cannot.”

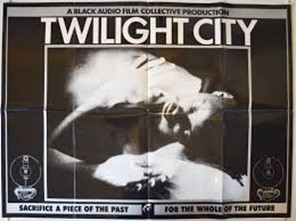

These three workshops broke away from traditional cinematic structures and demonstrated the complex ways in which memory functions for marginalised communities. In Black Audio’s Twilight City (1989), Olivia argues how she has to “sacrifice a piece of the past for the whole of the future.” Through the dynamics of memory, the workshops started their own visual archives where their films remain endless repositories of black British counter-memory.

Debunking Stereotypes

Their films countered national amnesia and historical forgetfulness (Hall 1978), challenging black British representation. Before, as the off-voice of Territories argues, they were “struggling to tell a story, a herstory, a history of cultural forms specific to black people.” Their works show the end of the essential black subject and place attention to the “diversity, not the homogeneity, of the black experience” (Hall 1993, 111-113).

These workshops opened a space for experimentation and offered upcoming generations a new cinematic language. Their works still speak to current conversations about race, identity, and representation, reminding us that the struggle for visibility and equity in the arts is ongoing. The exhibitions Life Between Islands (Tate Britain 2021) and Per-Akhan (Raven Row 2023) encapsulated this idea. This month it is worth remembering the powerful conversation they started and recognising how they transformed Black British cinema. Acknowledging this indicates how, “the living transforms the dead into partners in struggle” (Handsworth Songs 1986).

María Piqueras-Pérez is a PhD in Black British media. Her PhD research focused on black British media. She investigated the legacies and impact of the London-based black British film and video collectives Ceddo, Black Audio Film Collective and Sankofa. She has been a Visiting Researcher at the University of Westminster, London (September 2021-January 2022), at King’s College London (August-December 2022) and the University of Liverpool (July- December 2023). Maria’s research interests include–but are not limited to–Cultural Studies, Memory Studies, Film Studies and Postcolonialism. You can find her on Twitter / X HERE

Leave a comment