By James Harvey

Having spent several years immersed in the films of John Akomfrah for research purposes, I was very happy to read María Piqueras-Pérez’s excellent contribution on the 1980s Black British workshops movement, published on the blog earlier this month. Following on from this, I wanted to offer some insight on what came after the workshop period in the work of Black Audio Film Collective, at least. Following experimental archival works like the Expeditions series (1983-4) and Handsworth Songs (1986), and what Kobena Mercer described as ‘postcolonial tragedy’ (2016) in Testament (1988), Black Audio made Who Needs a Heart (1991) – a film filled with symbolic imagery and a deeply ambivalent reflection on the legacy of black radicalism as it has existed in recent British history. The film is also significant as a departure point – away from stories of post-imperial Britain and towards a consideration of transnational, Black Atlantic narratives. Seven Songs for Malcolm X (1993) was released shortly after Spike Lee’s celebrated 1992 biopic. Seven Songs is a film which repositions Malcolm X’s life and thought in a long history of pan-African thought and practices. Black Audio returned to the subject of Black American leaders with Martin Luther King: Days of Hope in 1997 and again with The March in 2013. These films represent a negotiation of the collective’s signature archival montage form within the constrictive parameters of television production.

Distinct from the earlier experimental aesthetics and the later developments to be found in Akomfrah’s museum installations, the 1990s is a period marked by the frustration of reconciling commercial demands with thematic and aesthetic preoccupations. This is encapsulated in Black Audio’s strategic repositioning as an independent film production company (Smoking Dogs Films). Despite this pragmatic shift, the era nonetheless provided a cohesive body of work on what Nicole Fleetwood has called ‘racial iconicity’ (2015). So overdetermined in the visual economy of late twentieth century US media, Martin Luther King and Malcolm X epitomise the tendency to either venerate or denigrate Black public figures. In the 1990s, Seven Songs for Malcolm X and Days of Hope brought the Black Audio neoexpressionist form to bear on this topic, reframing the social and cultural dimensions as a question of the aesthetic.

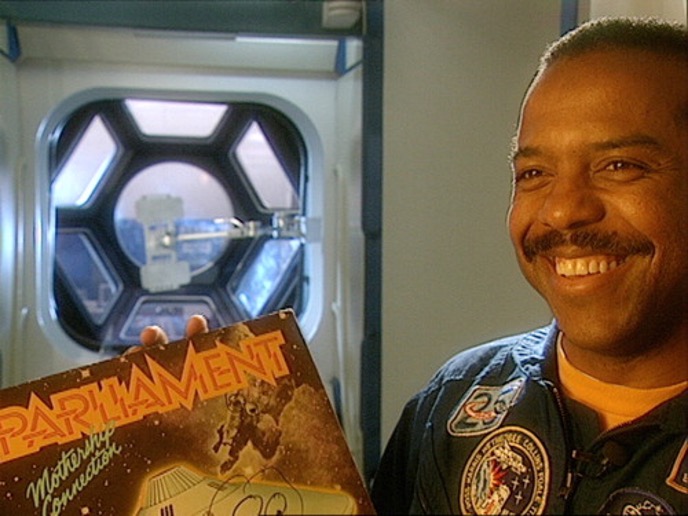

This period should not be understood solely as one of political critique, though. Black Audio also made the seminal Afrofuturist documentaries, The Last Angel of History and Goldie: When Saturn Returnz, as well as The Wonderful World of Louis Armstrong in the 1990s. It was clearly a time when Akomfrah and Black Audio were negotiating questions of racial iconicity as it pertains to Black public figures in the margins of popular culture. And by the 2000s, Akomfrah’s barely seen documentaries about Mariah Carey (The Billion Dollar Babe) and Urban Soul: Stories on the Making of Modern R&B, entered headfirst into the centre of popular culture. While apparently disconnected from the social and political concerns of civil rights subjects, these are films which reveal the mechanisms of what Cornel West termed ‘the new cultural politics of difference’ (1990) – a depoliticised but nonetheless unified demonstration of Black and diasporic subjecthood, breaching the threshold of the mainstream, with often unforeseen possibilities. The R&B films are “stories of Black success”, less concerned with questions of historic injustice and structural racism. However, the legacies of the aesthetic form developed through the 1980s workshops troubles the traditional imagery of racial iconicity, centring instead the images and sounds of Black Atlantic agency.

In the new millennium, Akomfrah began working almost exclusively in museum and gallery spaces, most recently commissioned for the British Pavilion at the 2024 Venice Biennale. These images have entered the comparatively rarefied space of the art world, exemplified by the academy’s embrace of this era (represented also by the 2023 Venice selection for Sonia Boyce and the major Tate show for Isaac Julien). However, perhaps the time is ripe for a reconsideration of the neglected 1990s period. As an extensive study of racial iconicity in late twentieth century Black Atlantic culture, we can discover a body of work that would influence the multitude of visual texts historicising Black public life in more recent years.

Dr James Harvey is a Senior Lecturer in Film and Media at the University of Hertfordshire. His research is preoccupied with the politics and aesthetics of film and screen media, with an emphasis on documentary, artists’ moving image and art cinema. He is especially interested in themes of race, coloniality and nation. James is the author of John Akomfrah (BFI Publishing/Bloomsbury, 2023), Jacques Rancière and the Politics of Art Cinema (Edinburgh University Press, 2018) and the editor of Nationalism in Contemporary Western European Cinema (Palgrave Macmillan, 2018).

Nicole R. Fleetwood, On Racial Icons: Blackness and the Public Imagination (New

Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2015)

Kobena Mercer, Travel and See: Black Diaspora Art Practices Since the 1980s

(Durham, NC and London: Duke University Press, 2016)

Cornel West, ‘The New Cultural Politics of Difference’, October, No. 53, (Summer

1990), 93–109.

Leave a comment