Mark Fryers

In recent years, the history of Black horror cinema has been recovered and rewritten. This post will contextualise two pioneering Black horror films in the lesser-known history of Hollywood cinema, highlighting the relationship between the mainstream and the margins in early Hollywood.

Oscar Micheaux is acknowledged as a pioneer of Black filmmaking. A successful writer, Micheaux founded the Micheaux Film and Book Company of Sioux City in 1919 and adapted his own novel, The Homesteader, for the screen in the same year. Micheaux’s educated Black and mixed-race characters were a response to the stereotyped visions of Black characters in mainstream films and literature at the time.

At this time, there were Black-only cinemas and films that catered for the multifaceted needs of their audience which ‘were important agents in propagating messages of racial uplift’ (Frymus, 2023: 248).

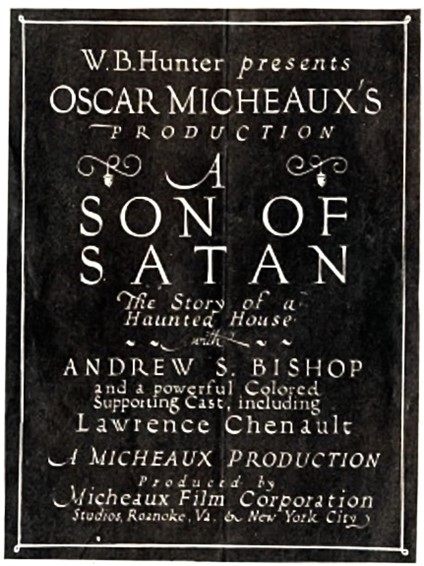

A Son of Satan was released around the same time that Universal were releasing a series of gothic horrors based on literary sources including The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923), and many others featuring Lon Chaney as characters with visible disabilities, which were often influenced by German Expressionism and interpreted as an attempt to process the trauma of World War One (see e.g. Bloom, 2019: 13). Satan dealt with trauma of a different kind. Micheaux wrote, directed and produced the film with the now recognisable premise of a man who accepts a bet to spend a night in an allegedly haunted house.

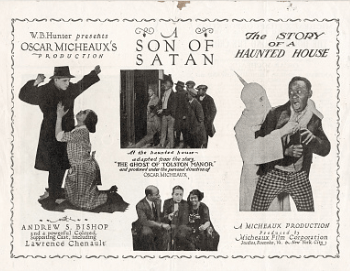

As with all of Micheaux’s films, white America took objection to several of the main themes, in this case the film’s violence and its interracial relationships. The film clearly engaged with political themes as a Ku Klux Klan member is killed onscreen. Although thought to be a ‘lost’ film, it now stands as a testament to the ingenuity of Black filmmaking in horror as a vehicle to navigate numerous states of disenfranchisement. The promotional material (Figure 2.) clearly shows the dangerous other as not a ghost in a white sheet, but a member of the ‘Klan.’

The depression proved to be the death-knell for Micheaux’s filmmaking career, and the mainstream continued to promote stereotyped Black characters in sound films of the era.

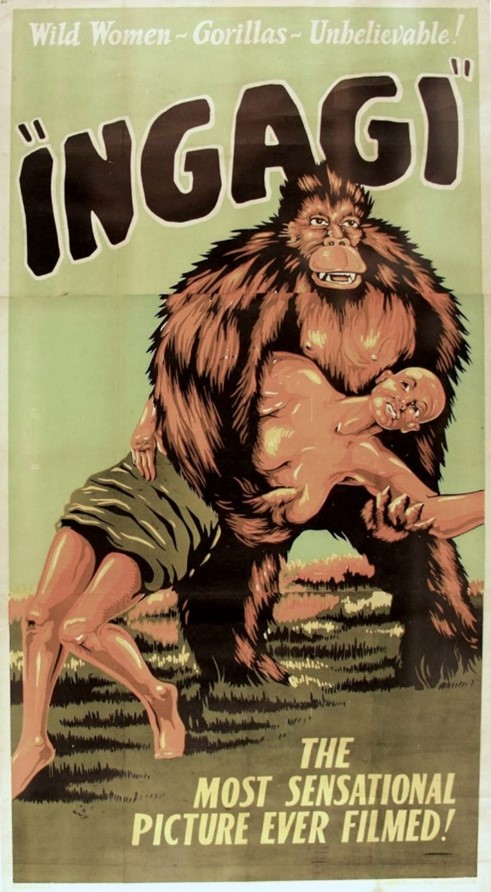

According to Means Coleman, ‘1930s horror displayed an obsession with “out of Africa” tales in which whites “conquer” or tame the continent’ (2023: 44). Another strategy of the time was to make films that blurred the boundaries of the travelogue and fiction. The travelogue was notable for promoting non-western countries and communities as ‘exotic’ and often savage, perpetuating problematic notions of the ‘other.’ One film that obliterated these boundaries is Ingagi (1930), billed as a documentary made in Africa, but actually a fake exploitation narrative filmed entirely in California (Figure 3).

It is noteworthy that the next pioneering Black horror film took the name from this earlier film despite no other affiliation. Demonstrating a regression, of sorts, from Micheaux’s pioneering days, Son of Ingagi (1940) was financed and directed by white investors and filmmakers who sought to exploit the economic opportunities of Black audiences, in a slight tale of a woman who harbours an ape-man in her house (riffing on the success of King Kong, 1933). The film crossed over, with the Film Daily noting an ‘Unusual showing of a colored picture to downtown white audiences’ (March 25: p.8).

Nevertheless, the film centres on Black characters, shown to be successful and educated, one of whom is a lawyer, in contrast to the greedy, white woman. Again, the notion of the ‘other’ in this horror fantasy is fluid. Progress is clearly not linear, but what is evident here is that there are examples, even within the horror genre, of more progressive representations of Black communities than were evident in mainstream Hollywood, as well as efforts to complicate the conception of the ‘other’ in these texts.

It might be worth considering that in both these cases, the ‘son’ of the title is significant within their contexts of Black cinema. Does this son represent an infant offspring of the mainstream, or perhaps a re-birth, the possibility of doing something new?

Dr Mark Fryers is a Lecturer in Film and Media at the Open University. He has published widely on film, television and cultural history and specialises in the intersection of maritime spaces and media, youth horror culture and British film and television. His forthcoming publications include a monograph on The Woman in Black (1989) and an edited collection on cybernetics in science fiction.

References:

Bloom, Clive (2019) ‘Introduction,’ in The Palgrave Handbook of Contemporary Gothic, Springer Press (eBook).

Coleman, Robert R. Means (2023) Horror Noire: A History of Black American Horror from the 1890s to the Present, London: Routledge.

Film Daily, March 25, 1940.

Frymus, Agata (2023) ‘White screens, Black fandom: silent film and African American spectatorship in Harlem,’ Early Popular Visual Culture, 21:2, 248-265, DOI: 10.1080/17460654.2023.2209942

Leave a comment