Alex Adams

The central conceptual territory of Gareth Edwards’ 2023 movie The Creator is a sci fi genre staple: humanity is locked in a bitter civilisational war with its uncannily humanoid machine creations. Despite the capacious potential for cliché that this may suggest, however, the movie’s novel emphasis on the realignment of its protagonist’s allegiances has unexpectedly progressive political implications, implications which make it – perhaps counterintuitively – one of the most interesting drone films of the decade so far.

At the start of the movie, Joshua (John David Washington) repeatedly asserts that the emotions expressed by the film’s robots – known as ‘simulants’ – are ‘not real’. The haunting screams of a robot searching for the long-dead humans it is sworn to protect are ‘just programming’; when he kills a robot, he insists that it is ‘off’ rather than ‘dead’. By the film’s conclusion, however, he recognizes their humanity, their authentic ability to feel deeply, to love and to fight for justice. The film’s central ethical gesture, that is, is the expansion of the category of ‘the human’ such that this category is able to embrace those of us who are dehumanized by humanity’s imperial war machine.

This gesture is characteristic of one of the major ethical projects of human rights and, by proxy, of social justice movements. In Inventing Human Rights (2007), Lynn Hunt writes that one of the most historically significant ways that human rights have been enabled is by emphasizing (in major forms of campaigning and representation) that everybody can feel pain – that enslaved people, for instance, can suffer as deeply and meaningfully as those who claim to be their masters – and that, as a consequence, everybody should be protected from this pain by a human rights system that applies to everybody equally. One of the driving insights of social justice movements, however, is the material recognition that these rights do not in practice actually protect everybody. The Creator, then, takes up a long-established task of demonstrating forcefully the violent injustices that are inflicted upon those of us who are understood as not ‘really’ having access to full human sensibility. Most importantly, the film’s project is to reveal the humanity of people subjected to sustained military violence under the auspices of ‘security’ and ‘peace’, perhaps one of the most important social justice tasks of our time.

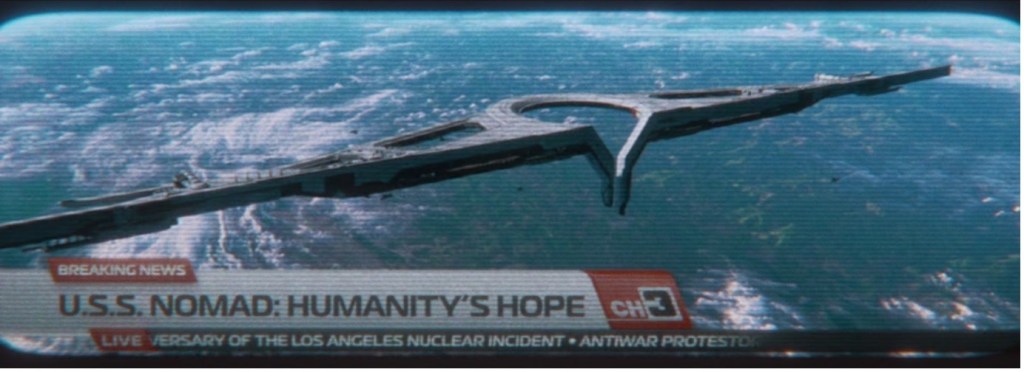

But it is not only Joshua’s recognition of the humanity of simulants, however, that marks The Creator out as unusual. His character arc also enables the film to articulate a certain anti-imperialism. As a converted agent of the Western military, Joshua sees the corruption, inhumanity, and moral failure of that military with especial clarity. Our sharing of his perspective enables us to traverse his political trajectory with him, and in the course of this transformative journey the Western counterinsurgency against the AI simulants of ‘New Asia’ becomes a source of ominous, impersonal horror. The Creator engages with many of the generic conventions of the contemporary war movie, but its engagement with drone warfare is most prominent of all. The Western military track down their AI targets using the fearsome aerial assault technology NOMAD, a low-orbit attack station which can surveil and strike anywhere on the surface of the Earth. Throughout The Creator, NOMAD is consistently evocative of today’s many military drone programmes; The Creator’s representation of this technology as a kind of sinister, oppressive death star carries with it a potent implicit critique of contemporary drone warfare.

A few words of context may help. What we could call the ‘first wave’ of drone films constituted a cycle of earnest single-issue thinkpieces such as Eye in the Sky (2015) or Good Kill (2014), movies which often articulated a limited critique of drone systems but which ultimately represented them as a necessary and defensible integration of cutting edge technology into contemporary warfare. The appeal of such films having reached a point of exhaustion, popular culture now most often addresses drone warfare more obliquely through genre pieces such as Netflix thriller Outside the Wire (2021), a near future speculative fiction in which a single well-placed drone strike averts the thermonuclear destruction of multiple American cities. Where a drone is an ambiguous object in films like Eye in the Sky and a heroic object in Outside the Wire, however, in The Creator the drone is a tool of state terror. Its approach is the approach of death from above; its targeting light a macabre warning of imminent atomisation.

At the film’s conclusion, Joshua detonates NOMAD in space, and this triumphant act of infiltration – an act that the film’s Western military or the characters of, say, Good Kill would no doubt consider an act of outrageous, indefensible terrorism – is the movie’s happy ending. Where other drone movies use a drone strike as their moment of cinematic climax, the spectacular narrative satisfactions of The Creator come from the destruction of a drone and all of the surveillant imperial violence that it represents.

The film also serves as a showcase of the limits of the liberal imagination. By reimagining Western military might as something that can be decisively defeated through the detonation of one vehicle, the film exhibits a utopian naiveté that undercuts its radical potential. The Creator’s central metaphor of a floating engine of death may well enable a critique of contemporary imperial violence, but its representation of that sinister technology as being fatally thwarted with one big bang fails to articulate the integrated and resilient scale of that very imperial violence. The techno-orientalism of the film’s representation of AI simulants, too, could be the subject of its own essay: for all that the film expands the category of the human, its use of robots as a rhetorical means of achieving this goal is far from unproblematic; its attempt to humanise AI, too, could easily be interpreted as irresponsible in a time when real-world uses of AI technology are, to use only one controversy as an example, colossally environmentally destructive. The trappings of genre convention place certain important limits on what The Creator can say. That said, the fact that it is trying to say these things at all makes it worth serious consideration.

Alex Adams is an independent scholar based in the UK. Their latest book, Kill Box: Military Drone Systems and Cultural Production, was published by Rowman and Littlefield in December 2024.

Leave a comment